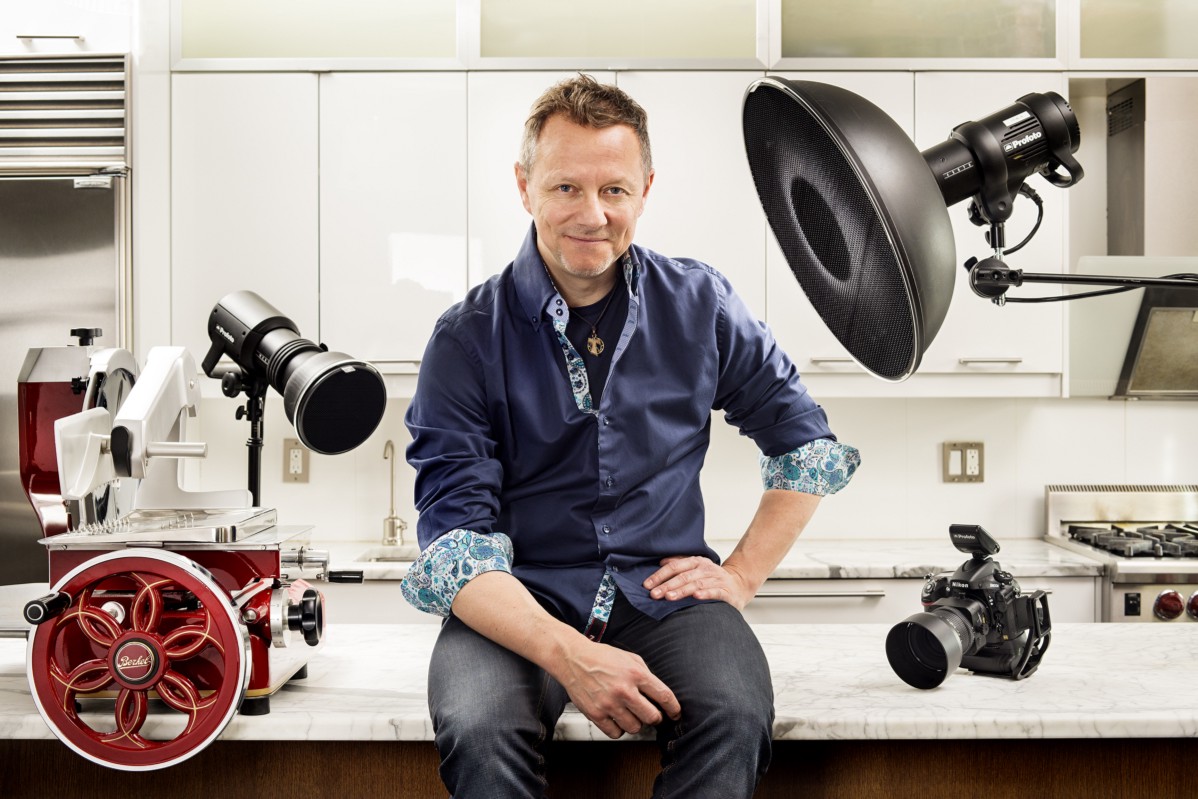

Describing Francesco Tonelli as a food photographer is rather like saying Pavarotti was a singer: both statements are perfectly true, but don’t come close to expressing the depth of their talent, nor do they do justice to just how hard they worked at it.

Like Pavarotti, Francesco is from Northern Italy. From early childhood he had a deep passion for cooking and, by the time he was 14, he was already working in the kitchen with his brother who was a chef. Over the next 20 years, Francesco developed his culinary skills by cooking in Italy, Switzerland and France. And he didn’t just cook. While in Milan, Francesco ran a couple of restaurants which meant that in addition to his time in the kitchen, he was also responsible for pretty much everything else.

Francesco’s experience led to him to be hired by the La Cucina Italiana magazine to develop recipes. As he remembers, ‘I actually ended up testing them (the recipes) to make sure they worked and then styling them for the photo shoots’. It was a very successful arrangement, and Francesco ended up working alongside food photographers for almost eight years.

Welcome to America

During his teens, Francesco’s two older brothers had both moved abroad: one to the US and one to Canada. Francesco had made numerous summer trips to visit them, frequently working at his brother’s restaurant in Montreal. The trips left their mark, and eventually Francesco packed his bags and left Italy for good.

Francesco explains, ‘I decided to look for an adventure in North America. I conducted several interviews in restaurants, schools and food companies throughout New York, Washington DC, Boston, Chicago and Vancouver.’

But the job he finally accepted was to teach at one of the most prestigious cooking schools in the world: the Culinary Institute of America — the other CIA.

Even for someone as experienced in the kitchen as Francesco, working at the CIA was relentless. ‘When I started teaching at the school, the pace and the nature of the teaching position was pretty demanding.’ The 14-day course had an average class size of 18 students, most of whom had never set foot in a professional kitchen.

Each day, Francesco would teach his class six or seven different dishes, one of each for a different cooking method’ (boiled, braised, sauteed etc). Each day the dishes changed, so the students only got one attempt to make each one. And if that wasn’t enough, every lunchtime ‘we opened the kitchen to feed around 100 people each day’.

Lesson Plans & Photography

It soon became clear to Francesco that he was going to have to create far more comprehensive course guides and lesson plans to prepare his students for the frenetic pace of learning. And that’s where photography came in.

‘It occurred to me that it would be useful to have the support of images, which in 1997 was not as common as it is now.’ Francesco decided that he would photograph the finished dishes so the students could see how they were supposed to look.

The problem was he didn’t have a camera. ‘I bought this Olympus D-500L — which I remember was less than a megapixel’. The iPhone 6 has an 8-megapixel camera.

With his new digital camera in hand (and set to fully automatic), Francesco began shooting his first food pictures. They were, in his words, ‘horrible’. But he persevered and gradually, over time, what started as just a way to improve his lesson plans became his new hobby.

Francesco had remained in touch with one of the food photographers he had worked with back in Milan. The two had become a good friends. Francesco reached out to tell him that he had bought a camera, and sent him some of his photographs of food. His friend’s reply was along the lines of ‘Wow, the food looks pretty cool. But man, you need to learn how to use the camera!’ So to help Francesco learn, the photographer sent diagrams showing him how to set up the lights, and how to create a simple home-made soft-box out of cardboard.

This article was originally written by James Bareham and appeared on Medium on April 4, 2015. You can read the rest of the article on Medium.